Ralph Permar custom turkey calls

The perfect pairing of aesthetics and utility

The known use of turkey calls, instruments designed to duplicate the various interpersonal discussions between boy and girl turkeys, has been going on for more than 8,000 years. The early contrivances were wholly functional, a craft born of long experience in the woods and from the urgent necessity to ward off hunger.

Turkey hunting today is one of the last of the real “hunts,” as opposed to those hunting events, which can be described as more of a “shoot.” The hunter has to enter tree-shrouded turkey territory stealthily and keep very still and make sounds convincingly enough like a hen turkey to lure a wary old gobbler within shotgun range. It is usually a solitary sport devoid of witnesses, which is a good thing due to the excessive opportunities for the many forms of humiliation this sport affords. Some facility- with a turkey call is usually an essential element of a successful turkey hunt.

Before the advent of mass-produced turkeys calls, the individual hunters constructed their own. The forms evolved according to how they wanted them to sound. They were hand-made and individually tuned like a fine musical instrument. In general, turkey calls are designed to imitate a series of wild turkey sounds called yelps, clucks and cuts. Other than a few mechanical oddities, turkey calls are either friction calls or air calls and their manufacture has had a long and distinguished history in the Palmetto State, by names such as Archibald Rutledge (1883-1973) of Hampton Plantation near McClellanville, South Carolina, who handcrafted a line of friction calls, box yelpers, under the name “Miss Seduction,” which he advertised in sporting magazines and sold commercially for around $5.00 apiece.

More recently, Greenwood, S.C. native, and legendary custom call maker, Neil Cost (1923-2002) was best known for his box yelpers especially one of his designs known as the “Boat Paddle,” because of its long boat paddle shaped striker. Cost’s calls are now selling for big money to collectors who are lined up and eager to buy them.

But perhaps most famous of them all was Henry Edwards Davis (1879-1966) a lawyer and turkey hunter from Florence, S.C. and author of the much vaunted book “The American Wild Turkey,” (1949). He built box yelpers and trumpet yelpers mostly for himself, but also for a few of his hunting companions. His own personal trumpet yelper passed through a few hands after his death and was sold to a collector in 2005 for an eye-popping $55,000.

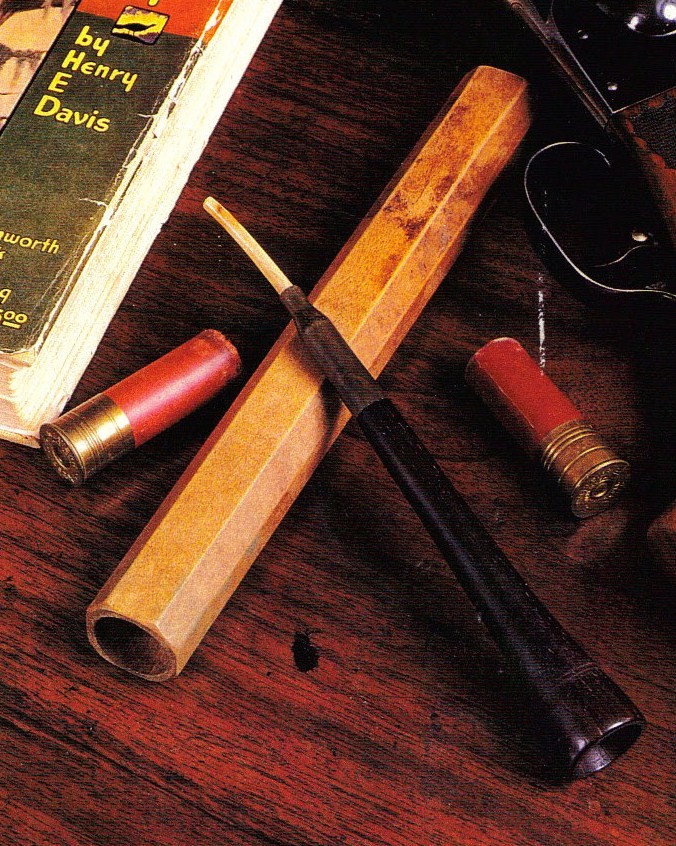

Burton Moore 111, partner in the Audubon Gallery at 190 King Street, is a devotee of turkey hunting. He is also a knowledgeable aficionado and purveyor of turkey hunting collectables such as custom calls, carved decoys and books. In his quest for notable examples of the call making craft, he learned of Ralph Permar, a turkey hunter from Old Zionsville, Pennsylvania, who specializes in making trumpet yelpers. In addition to an impressive line of his own Roanoke River Basin original designs, Permar also makes reproduction vintage calls made by some of the most respected craftsmen in the history of the business such as Austin Fulbright, the Turpin family and Henry E. Davis.

Other than the obvious absence of the battle scars of use, the reproductions of the old masters are perfect, fully functional replicas of the originals and, like a fine carved wooden decoy, they have a look and a feel all their own. When Moore sent me an email image of Permar’s Henry Davis reproduction trumpet yelper without any caption, I was able to identify the original designer immediately for I have held one of the original Henry Davis trumpet yelpers in my hands. In the process of editing Davis’s hunting memoirs for publication, I came to regard him almost as an old friend. Actually holding something he had made with his own hands well over half a century before was a truly remarkable experience. I previously had a similar singular moment when I was able to use Mr. Davis’s 100-year old custom-made WW Greener shotgun to take a turkey on the same Pee Dee River plantation where he had also hunted turkeys.

In the 11th chapter of his book “The American Wild Turkey;” Davis wrote very specific directions on the dimensions and construction of his trumpet caller and Mr.Permar who has been making turkey calls since 1995, followed them to the letter, except in the respect that Davis used cocobolo wood for the horn of the trumpet and Permar used African black wood to make it more closely resemble the darker patina, of the older call. The trumpet is joined to the turkey wing bone mouthpiece by a fired .257 Roberts shell casing. The original Davis trumpet yelpers were stored in an octagonal wooden case to protect them when out in the woods and fields. Permar said that it was actually more difficult to make the one-piece cherry wood case than it was to make the call.

Mr. Davis who preferred trumpet yelpers to any other type of call, also used yelpers made by the Memphis call maker Tom Turpin, whose designs have also been reproduced by Permar. His interpretations of vintage calls as well as his own designs stand out as some of the best examples of this form of folk art. Numerous awards at competition throughout the country have repeatedly validated the quality of his work. Permar, who also has a scholarly interest in the lore of turkey hunting, said in 1994, he became fascinated with the design and patina of the instruments used by the old time turkey men to call birds to the gun.

The Audubon Gallery in Charleston is the only retail establishment where a person can walk in and purchase one of these limited edition calls. Moore said he is carrying this line of classic turkey calls because they fit nicely with the old and new duck and shorebird decoys, sporting books and sporting art he already displays in the gallery. In addition to the Permar trumpet yelpers, he also carries examples of creatively designed friction box yelpers by other craftsmen, which are made of combinations of domestic and exotic wood types, some of which display elaborate decorations such as inlays and hand checkering. It is said that imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. That old turkey hunter and polymath of the Pee Dee, Henry E. Davis would be proud.

Ben Moise is a freelance writer and editor of “A Southern Sportsman: The Hunting Memoirs of Henry Edwards Davis, “as well as the author of his own memoir, “Ramblings of a Lowcountry Game Warden.”